Best Selling Author

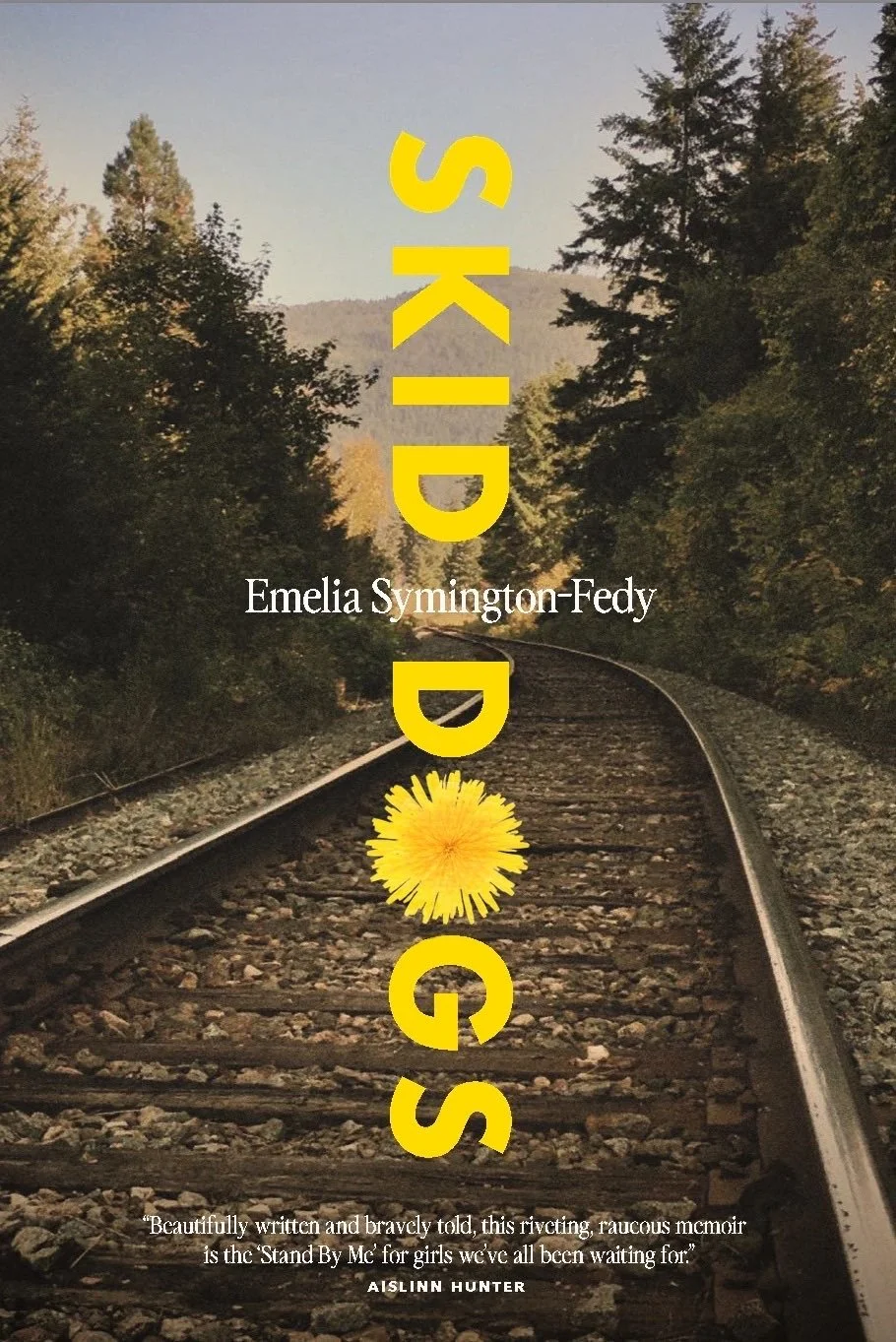

Skid Dogs

By Emelia Symington-Fedy

“I can’t remember the last time I read a book so brave. Maybe never.”— Ani Difranco

“I fell hard for the scrappy, funny, honest, resilient young heroine of Skid Dogs, and the wise narrator who mediates her story—an essential tale of girlhood survival.” —Melissa Febos, author of Girlhood, winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award

“With plenty of Juicy Fruit, padded bras, and pot smoke, the narrative begins as a nostalgia-tinted reverie before evolving into a devastating portrait of the pre-#MeToo era from someone on the other side of it. The author’s candor and courage will move readers regardless of when or where they came of age.” —Publishers Weekly

On Halloween night in 2011, a girl is killed on Armstrong’s railroad tracks and Emelia returns home to comfort her terrified mother as her community reels in chaos. Skid Dogs tracks the nuanced and granular coercion that permeates girlhood. A window into how girls behave before the male gaze lands, this memoir captures girls at their most unruly and free.

This unflinching reckoning of teenage rape culture tells the dark and hilarious true story of a thirteen-year-old and her girl gang before they have to turn against each other to survive. Set in the life-loving and rowdy early 1990s Emelia braids the early teenage years of her girl gang throughout the real-time events of 2011 when she returns home as an adult to witness the terror her hometown is going through while trying (and failing) to care for her dying mother.

Full of the wry humor they learned on the tracks, Skid Dogs advances a necessary cultural reckoning about pleasure, promiscuity, and consent, poking back at what Emelia previously didn’t dare admit, that assault was common and put up with. Now, back at the scene of the crime, Emelia is forced to recognize the constant and often painful mishandling of her own teenage body. Maybe this is why the old gang hasn’t talked in twenty years? And why she still looks over her shoulder at night? In this raw and wry debut, Emelia holds her hometown close and accountable, revealing the personal ways misogyny shows up daily, making the harm done blatant, grotesque, and sometimes- by necessity- comically absurd.

-

You know a book is both meant for you as a reader and well-written when you feel regular twinges of discomfiting self-recognition as the story sinks into your blood. I can’t remember the last time I read a book that so accurately and painfully reminded me of my own adolescence, even if mine was in Vancouver and that of Skid Dogs takes place mostly in Armstrong. Evelyn Lau’s Runaway and Yasuko Thanh’s Mistakes to Run with, say, were too extreme in their evocation of sex work and drug addiction to be relatable to a typical teen girl of the era. Skid Dogs bares the hum-drum awfulness of just being female as one’s sexuality burgeons in the shadow of male aggression, misinformation, the accepted ecosystem of misogyny. Emilia Symington-Fedy was lucky enough to be part of a group of girls who had her back, much of the time at least prior to the later grades, and who gave her a sense of being a collective sufferer of often unwanted male attention and both the random and planned agonies of the female body. I recall much more isolation, my hormones and low self-esteem driving me directly into a male world that excluded other girls as they were potential rivals or just simply didn’t provide that fucked dopamine rush of being wanted by boys, however momentarily.

Skid Dogs, a memoir that reads like a page-flipper of a novel, veers back and forth between two temporalities: the first is 2011-2013 post-murder of a teen girl, Taylor, on the tracks in Armstrong as Symington-Fedy’s mother is dying slowly from cancer, and she must return regularly to care for her while, at the same time, straining to create a documentary on the tragedy and 1991-1996, Symington-Fedy’s high school years in Armstrong, during which she meets the “girl gang” of Bugsy, Aimes, Cristal and Max, struggles to navigate pledges, sexuality, shame, the drinking culture, school, her younger brother Grum’s presence, and her mother’s initial cancer diagnosis, along with other issues resulting from her parents’ divorce and her own rebellious tendencies. At first, I had a little trouble flowing into the tale and becoming connected to the characters, as the allusiveness of the era overwhelmed, the familiarity in references to Esprit and Les Mis and Du Mauriers and slushies at Sev. Everything blended into consumer brands and the senses. However, before long I was compelled by both trajectories. Here’s a sample from each timeframe to give an idea of Symington-Fedy’s facility with sketching engaging scenes:

1991 on the first time Em gets drunk:

Tilting back, I drank three big gulps. My eyes watered fire. Leaning forward, hands on my knees, I dry-heaved but didn’t puke…The sky was light blue, on its way to dusk, and the air smelled of the sticky buds that grew along the ditch…I chugged until my stomach burned.

2012 on the state of Armstrong once the killer is apprehended:

As if a lid has been lifted off our valley….We must look like a town of foals, wobbling around on too-long legs…the wanted posters are ripped down…Even the staples are taken out of the telephone poles. Engines rev as kids open up their garages…[but] even though the new lights that hang along the fenceline are bright, they don’t penetrate the shade that edges the path.

In both these randomly-selected excerpts, one can hear the poetic talents at play in the prose, the consciousness of sound in knees/heaved or penetrate/shade, the focus on the crucial senses through which one can more wholly enter any experience and the similes, such as the comparison of the townspeople to foals, that serve to enlarge and deepen the vision of this key moment of release and re-birth within traumatic times. The Douglas and McIntyre Press Kit interview with Symington-Fedy is incredibly poignant in revealing her hopes for this memoir. She states that her intention in writing this book is so “the fourteen-year-old girl like me out there might make different choices…to witness that 30 years later, this mishandling of their bodies now, will be a problem. They will have long-term pain.” And although I doubt somewhat whether a 14-year-old would be able to truly absorb the lessons in this vital narrative, I know that for myself as a reader around Symington-Fedy’s age, it was brutally essential for me to re-envision that time when so much impact happened that felt like nothing, but that became immeasurably much in the future.

I almost felt embarrassed at my younger self who also believed, as the narrator recounts, that girls are instant sluts for yielding to male incursions (“Twyla was the first official slut of grade eight…She’d put herself in a no-win situation by being alone with him in the first place…all the dick licking and bikini-line waxing she’d have to do now”), that if a girl yields to sex then she will ensure commitment from a boy (“A hot liquid shot out of his penis down the back of my throat…I wiped my mouth…He likes me. He’ll want more”), that girls aren’t supposed to receive wanted pleasure but must see sex as “the action of ticking another box off the list,” and that even in adulthood, sex is the tool of assurance and power, as when into her thirties, the narrator thinks an “old thought” while she’s worried about her new partner’s core fidelity to her: “If I sucked his dick he’d come over just fine.” I truly don’t remember ever reading such poignant and raw summations of the irrefutable toxicity of being female in this culture of male entitlements. The notion that a girl is fixed in a reputation, whether based on truths or fables, from the get-go and will have a hard time, perhaps even a lifetime’s worth, of shaking it or persisting in a state of determined indifference. As Max comments nearer to the memoir’s end, reflecting on the above-mentioned Twyla’s pigeon-holing as a slut: “I just wonder who gets to make these decisions, ya know?”

Today, it’s even scarier for teen girls in certain ways, as while they may have more information (we had so little in the late 80s/early 90s in Catholic school that many girls in the class got VDs and/or pregnant. Em, at least, evinces much awareness of birth control in the tale!), there is more pressure to sexualize themselves from social media, and more evidence of their potentially sordid activities that can haunt them for the rest of their lives. Women of my generation frequently comment to each other how lucky we were that there’s no media proof of our abuse. Wow, how fortunate we are (she muses sarcastically). The only “dignity” the narrator seems to discover for herself as a needy teen is by becoming the one who is “ravenous,” not the one who is passive and thus, powerless. Oh, how relatable. Yikes. I won’t tell you how the memoir ends but it’s full of hope for a healing between generations, spouses, friends, and, most importantly, with the self. Skid Dogs (the teasing name the girls eventually dub each other) is rich with harshness and yes, with humour, which Symington-Fedy calls, in the Press Kit interview, “revolutionary” and also, “a sharp weapon when needed, too.” - Catherine Owen

-

Aching and funny new memoir- by Janet Smith

VANCOUVER AUTHOR and theatre artist Emelia Symington Fedy journeys back to her small hometown of Armstrong, B.C. for her new memoir Skid Dogs.

The book moves between the harrowing news of the 2011 murder of a girl on the train tracks in the farming town—and Fedy’s race to leave East Van and get home to her ailing mother, and the writer’s own experiences as a young teen in the ’90s, hanging out on those same tracks with her friends.

The book is a fearless, uncomfortable, but endlessly relatable confrontation of the sexual coercion, aggression, and assault that surrounded her just as she and her friends were figuring out who they were. Skid Dogs ends up being an unfiltered rumination on consent, and a time and place when girls were blamed for whatever happened to them if they got drunk. But it’s also a tender portrait of what it’s like to grow up and the freedom found through friendships—all punctuated by vivid period details like Short Stop slushies, Walkmans, and the smell of Dippity-Do hair gel, Herbal Essence shampoo, and BodyShop Dewberry perfume.

Those who have watched the Studio 58 grad’s plays (Trying to be Good, Through the Gaze of a Navel) or listened to her CBC Radio broadcast essays will notice a similar blend of laugh-out-loud comedy and aching honesty.

Stir caught up with her in the Shuswap, where she’s now living with her own young family after spending years as a well-known figure on the Vancouver theatre scene.

After so many years in Vancouver, how did you end up in the Shuswap and did you feel drawn back to the smaller-town life you write about in the book?

I was raised in the Shuswap. I left the day high-school ended. So, for me, this is a returning—something I never thought would happen by choice. But, my children were becoming “city kids”. For “country folk” being a “city kid” means you’re scared of dirt and wildlife and space to roam and I wanted them to have the skills to be adaptive to difference and discomfort. So, I decided that because the first half of their life had been spent in the utopic bubble of East Vancouver, with similar politics, class and lifestyle as our neighbours, I wanted the second half of their childhood be more rural, interacting daily with people who don’t hold the same beliefs as us, even might have counter-beliefs, but will happily plow our driveway at first snowfall. They need to learn the skill of building complicated relationships, relying on neighbours, and appreciate something as simple as “seasons”. They love the snow. They love their dog. They miss having access to what they want when they want it. I think it’s a great thing. And, I can feel the spirit of my mom cheering me on. She’d be so happy for us.

Was it the real-life tragedy that happened in your hometown in 2011 that first made you dig back into the sexual coercion and aggression that permeated the culture of your ‘90s teen years? Or was it something that had been on your mind for a long time?

Standing at the spot where Taylor was killed, the same tracks I grew up on, I immediately understood that this physical place—which had only ever been a source of comfort—had been ruined. The phrase that ticker-taped through my head was, “Where will all the Armstrong girls go now to feel safe?” It was this question that made me realize that in the 1990s we had experienced sexual violence and danger throughout our girlhood too. It was culturally accepted and we’d survived—but we’d be hurt. So, to honour Taylor, and push the conversation forward, I’m trying to start a more nuanced and active conversation about violence against women. Not be frozen by the horrific stories we know are brutal and wrong, but to start bringing to light the current, daily, ongoing reality of rape culture, which includes hilarity and pleasure.

How were you able to travel back to your 13- and 14-year-old self, and get so vulnerable with her, stepping back into her shoes—or button-fly Levi’s?

Lots of googling “Body Shop perfume,” and “most popular 1991 jeans,” and going down internet fashion wormholes. But honestly, the thing that made remembering easiest was reconnecting with my girl gang. After a few hours on the phone every few months of writing, my mind would overflow with the cackling and smells and hysteria of us. Whenever we spoke we returned to being 13-years-old again. We took on the voices, we had the pet names- it all came back effortlessly. And sometimes our memories differed and we discussed that, but mostly we’d spend the calls laughing at the ridiculousness of being a kid, before we knew we were being watched. That was the revelation actually, that amongst all the dark, shocking memories, it was the most joyful ones that prevailed.

Writer Jenn Ashworth wrote, “Some days it feels like writing truthfully about her own life is the most subversive thing a woman can do.” Do you feel like your fearless honesty can be empowering or freeing?

Why else would I eviscerate myself in public? I’m not dancing like no one’s watching. I’m praying that the dance reaches and transforms people. I’m a theatre artist by trade. Making autobiographical art is my form of activism. I use myself—shame, discomfort, fear and raucous indignation—to speak the truth of what I assume is many. I’ve had a lot of women, age 65 and age 15, tell me that they relate to the reality of Skid Dogs but they’ve never put words to it before. I start with a spark, a question: in this book the question was “If it’s not rape, what’s the word for what happened to us?” And through investigating, remembering, and turning the question slant, I try to come up with a fulfilling answer. Now, I didn’t find a word for the banal, relentless picking over of my body when I was a teenager, but I’ve developed clarity that it happened as part of a much larger cultural issue than just me in my small farming town. That discovery in itself brings healing.

Was it just as difficult for you to relive and dissect the conflicted relationship you had with your mother—something anyone who’s been a teenage girl can relate to?

This was the content I held myself to the fire for. My mother’s relationship was the one I wanted to most understand and repair. How can you resent the woman that made you? Recoil at her touch and find her simple presence irritating? I waited a few years until after mom died to publicly reflect on how I mistreated my mom. For the first few years it was only blinding shame. Now, I see a girl in profound pain, lashing out where she felt safest, and my strong mother holding that anger for me. The truth that I’ve come to is that my mother probably saw and knew why my behaviour was sometimes so hurtful, and she took the blows, as I do for my children now—that’s brought some relief. The only relationship in the world that lets you be your darkest self is motherhood. And when you know better you do better. Skid Dogs might be a warning cry to women who still have moms—she will be dead for longer than she was your mother, take her shit, hug her little body, so that when she leaves you know you’ve done your best. Obviously, it’s not as simple as this, but sharing our complex relationship, and my part in it, has been a way to turn my regret into action.

How has theatre informed your memoir writing, and where do both sit in your practice—are they separate or intertwined?

What a lovely question. Theatre is live. Theatre can grow and change with an audience in real time. The audience, in fact, is necessary to making this happen. Writing a book feels more like a solo venture. I can’t try a joke out before opening night. I can’t experiment with the risky line and cut it later. It’s all out there—a snapshot of my brain in time—forever. That’s terrifying to me. I was unprepared for the vulnerability hangover this book brought. I’m used to being clapped for- or poorly reviewed- and then taking that info and making adaptations to make the art better. I read Skid Dogs now and think “GAHHHHHHHHHH I should have used the word ‘last’ instead of ‘only.’ NOOOOOOOO, I shouldn’t have cut that line.” And there it is, in print, forevermore. There’s an ownership of the work that’s more confronting than theatre. That said, theatre can get 50-200 bums in seats per night and a book has no limit of readers. I don’t think I even answered your question. How’s this: Ephemerally, the purpose of all my art is an attempt to disrupt and make social change. But technically, in writing there is right and wrong—there are rules to follow, like grammar, which makes the forms very separate in my brain.

You have kids who are growing up now: do you feel like things have improved around consent and empowerment for teenage girls, especially since #MeToo? Do we still blame girls who get drunk for what happens to them?

Yep. We sure do. I’ve got teenage girls in my life and I’m sorry to report it may have gotten worse. A girl giving a boy oral sex is now as common as a first kiss—and that may be a consensual act, but the problem is that it’s not reciprocal. With porn so accessible, boys are being trained at an even younger age that girls’ bodies are to be practised on. If porn showed men giving women pleasure and having a mutually shared experience, great. But it doesn’t. Women are the objects for the subject. It’s archaic and ridiculous that we still smile and bare it. It’s also rude that “not all men” stops at rape. Maybe you didn’t hold her down. But did you ask? Did you keep checking in? Was she drunk? Were you careful and sensitive? This is what I demand of men, and what I want girls to demand of boys, my own included. My best friend has daughters and the only rule she’s taught them is: are you receiving as much pleasure as you are giving? It’s pretty simple really.

Why’d you write Skid Dogs?

It's a pretty dark book. I don’t hold back and I tell the story as grotesquely and relentlessly as I experienced it. But the higher purpose of Skid Dogs is to be bolstered by “Girl Joy”—that brief window in a girls’ life, when she’s with her best friends, wild and brash, with no idea that eyes are tracking them. That is freedom. I want that moment of power remembered— so that as grown women we can re-create it, and so that the girls on their way up can keep the window open for longer- could we imagine- for forever.

-

“Sugar, and spice, and everything nice; That’s what little girls are made of.” So goes the old verse that, in spite of its antiquated views on gender, remains a popular nursery rhyme. Girls have come a long way since Robert Southey committed those lines to the page back in the early 19th century, but there are still some forms of girlhood that are rarely depicted in popular media. Girls in books or films might be catty, but they’re rarely allowed to have deep, meaningful conflict. They might be funny, but rarely raunchy. They might be sluts or prudes, but they rarely get to be ambivalent about their sexuality. They might, in short, be girls, but they rarely get to be fully human.

That’s not the case, though, for the teenage girls in Emelia Symington-Fedy’s memoir Skid Dogs. They’re gross. They’re horny. They crack off-colour jokes (like, really off-colour jokes). They struggle – sometimes individually, sometimes together – with what it means to crave male attention in a world where most of the boys and men seem hell-bent on objectifying, coercing, and even assaulting them.

Symington-Fedy’s narrative runs on two tracks: one that begins in 1991 when, at the age of almost 14, she moves to a town in rural British Columbia and meets a new group of friends, and another that begins in 2011, when an 18-year-old in that same small town is murdered on the railway tracks where Symington-Fedy and her friends hung out. Paired storylines like this can be tricky, a challenge for authors to keep the stakes high enough and the plots paced appropriately so that readers remain engaged with the parallel accounts, but Symington-Fedy is a skilled enough writer to navigate this. Both timelines in Skid Dogs are riveting right up until the last page.

The later narrative also involves Symington-Fedy working through the challenging relationship she has with her mother. Theirs is a dynamic that may be familiar to girls with mothers who were influenced by second-wave feminism. Symington-Fedy’s mother is fiercely independent, a sort of homesteader who does her own renovations and is keen on raising chickens and canning. But when, at 14, Symington-Fedy gets blackout drunk and likely endures some kind of sexual assault, her mother is more angry and embarrassed than sympathetic. Pointing to an old school picture of her daughter, Symington-Fedy’s mother says, “They did whatever they wanted to you. I’ll never be able to look at that girl again.” In 2011, Symington-Fedy is also trying to quell her fear and rage over her mother’s terminal cancer, often making her mother the target of her outbursts. In spite of the difficulties, it’s clear that they love each other fiercely, even if that love sometimes is expressed as anger.

Symington-Fedy’s prose is keen and unsparing, especially when describing her own motivations and behaviour. She’s not one to let herself off the hook, even in moments when it would surely have been tempting to. Her writing can be screamingly funny, and in serious passages she never resorts to sentimentality. Every emotional moment feels fully earned.

Skid Dogs is so much more than a coming-of-age memoir. It’s an examination of the dangers and joys of girlhood. It’s a sober look at the way our culture treats women’s bodies, particularly young women’s bodies. It’s a close-up on the social dynamics of teenage girls, one that never shies away from the disgusting or difficult. But mostly, it’s just a really, really good read.